The Black History of Memorial Day and the White History of Suburbia

Links from Time Magazine and RetroReport (following the trail of Substacker Chloé Valdary)

There are two reasons to follow the link that

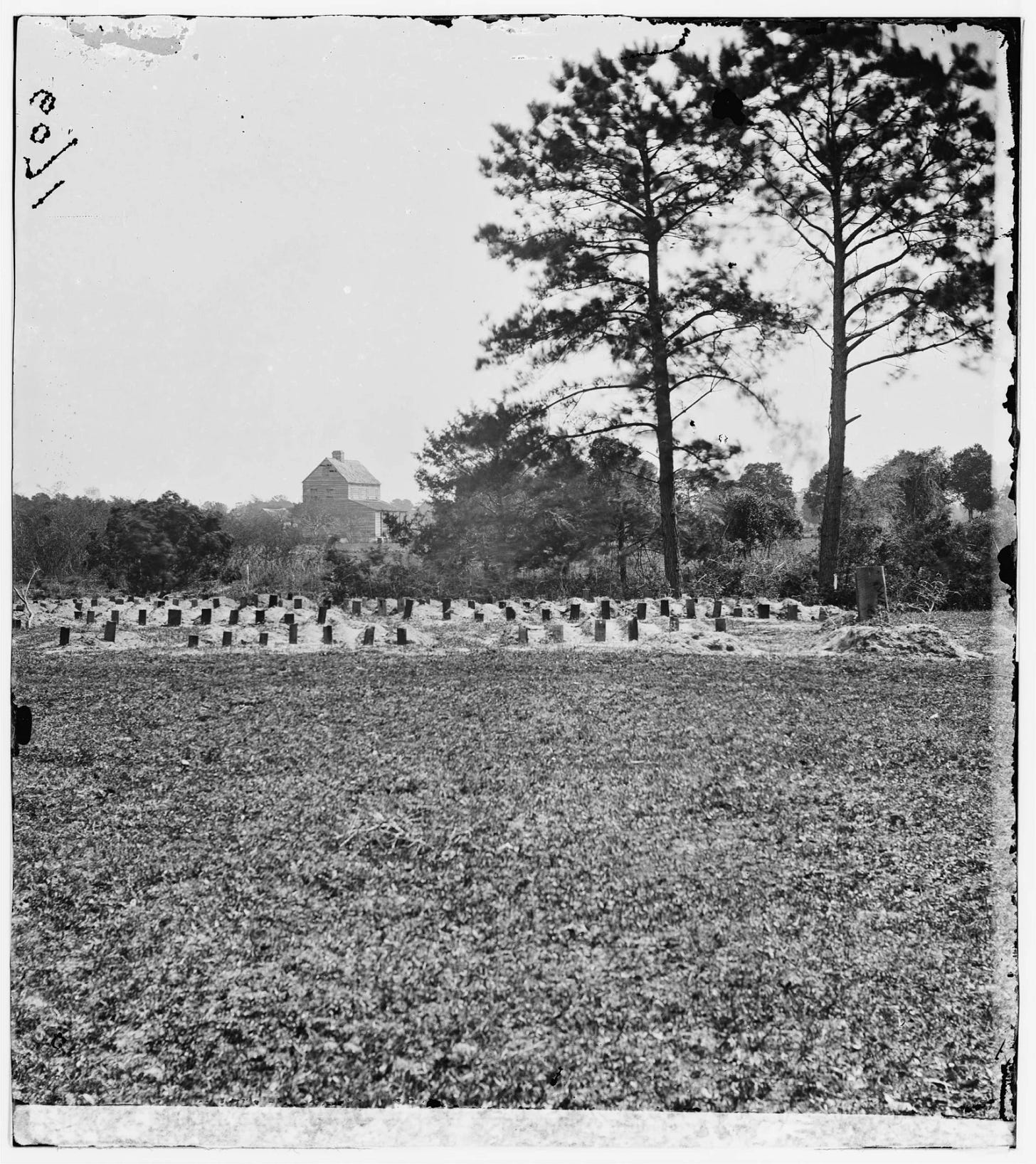

shared in Substack Notes on Memorial Day. The first is to learn about “The Overlooked Black History of Memorial Day,” the subject of the Time article that caught the attention of the author of Chloé’s Newsletter. The second is to view a 10-minute video from RetroReport titled “Whites-Only Suburbs: How the New Deal Shut Out Black Homebuyers.” I’m going to break with my usual pattern in this newsletter — keeping it simple; just the links — because there are so many layers behind the second link. See if you think, as I do, it is worth peeling back more than one of these layers to tell the PeaceLinks version of this story.First: Memorial Day. There are multiple claims about who honored Union soldiers’ graves first after the Civil War, and which of those events belongs to the history of Memorial Day. The Time article shared by Valdary zooms in on an event that precedes other origin stories and involves substantial Black participation and organization. Less than a month after the end of the U.S. Civil War, thousands of people, Black and white, participated in a memorial event at a Union cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. To learn about that event, click the photo below to jump to the Time magazine story by Olivia Waxman, “The Overlooked Black History of Memorial Day.”

Once you get to the Time website, you may see a sidebar, as I did, for “The History You Didn’t Learn,” by RetroReport. In case you don’t see it, I’ve attached “Whites-Only Suburbs” below. This video has all kinds of interest for PeaceLinks, some of which requires elaboration from additional sources below the video summary. Not least among the points of interest is that there is something anyone can do right now to push back against the racial restrictions to home ownership that took strong root in the past and affect multigenerational family wealth in America now.

In the video, the RetroReport team explains how F.D.R.’s New Deal encouraged banks to make affordable home mortgages but restricted those mortgages to white homeowners, so that the historic expansion of the middle class in the middle of the twentieth century was, by statute, limited to whites. This is not a new story, but it is well and succinctly told here, with a single neighborhood in Silicon Valley for an example.

The purpose of PeaceLinks is to collect and preserve internet nuggets on peace, the middle ground, and the spread of decency. Maybe I need to add the term “cooperation.” Both of these stories — of a Union memorial and a neighborhood confronting its racial restrictions — show cooperatives trying to practice decency and dignity-for-all. Keep scrolling for a summary of the video, a related NPR link, and a closing note about the cooperative pre-history of this particular California subdivision.

As a habitual re-reader, I love video summaries to remind me of key ideas and help me find them for replay. You can skip the summary if you prefer. It’s here:

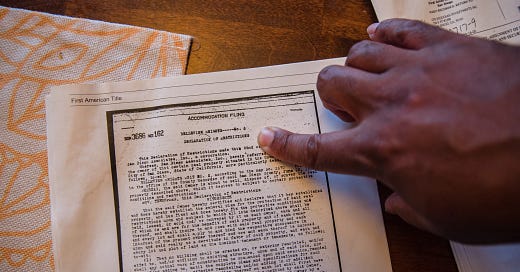

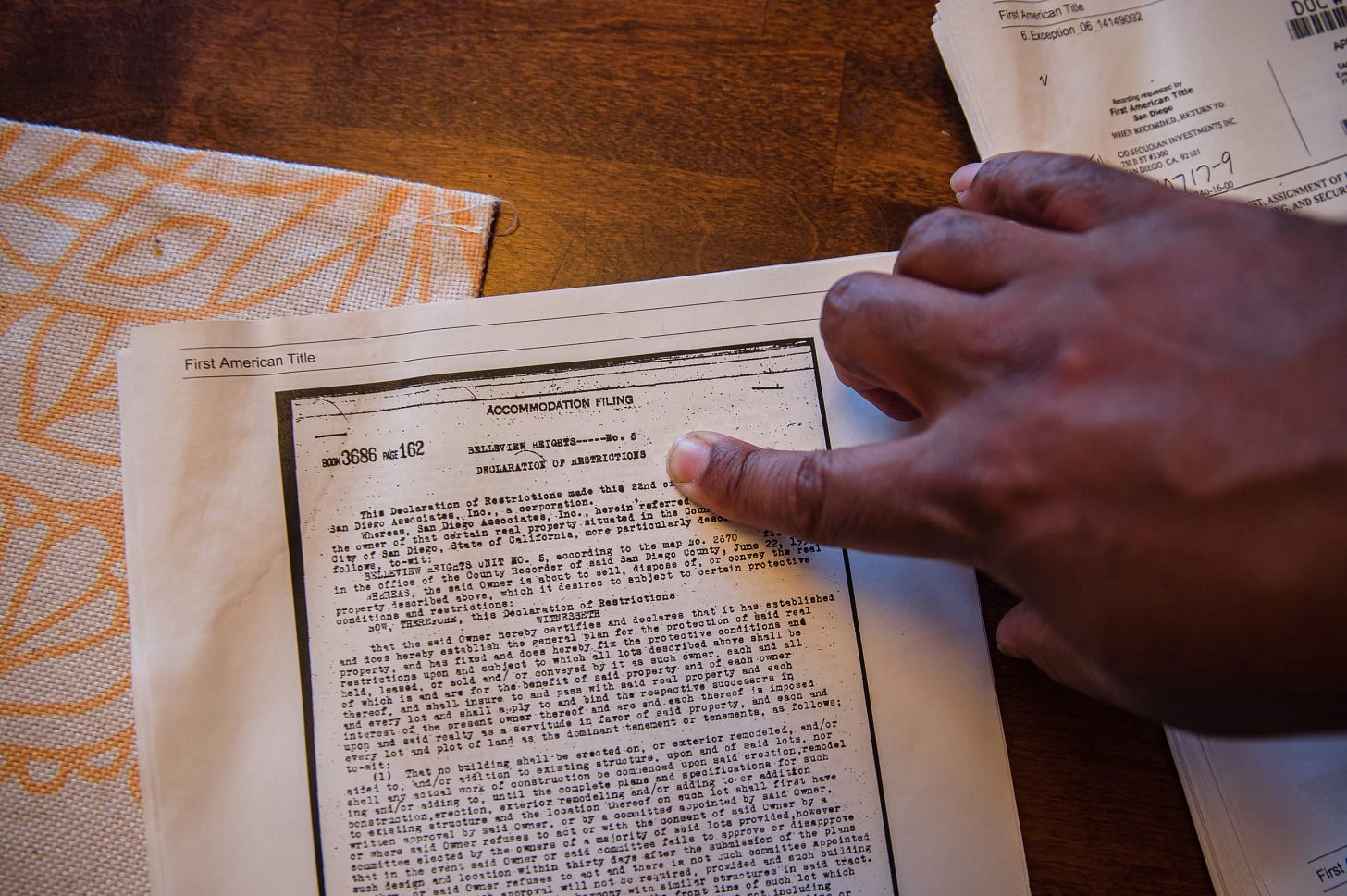

Introduction - A woman buys a home in the Silicon Valley subdivision of Ladera and discovers that her deed comes with 70-year-old racial restrictions no longer legal. Narrator and producer Erik German digs into where these restrictions originated.

1:30 The New Deal is remembered for progressivism and inclusion.

2:10 On mortgage lenders “redlining” neighborhoods

2:50 Ladera era 1: plans for a mixed-race cooperative community.

3:30 Novelist Wallace Stegner was one of the original investors. The group also included two Black families. The mixed-race co-op could not get mortgages. (See bottom of this post for the story as continued by Stegner’s biographers.)

3:35 Federal Housing Administration: template for race restrictions; no mortgage insurance to banks lending to Black homeowners.

4:05 Ladera era 2: a private developer built a whites-only subdivision.

4:18 - 5:55 Two family experiences of housing discrimination in the Palo Alto area.

7:01-8:40 The wealth gap between Black and white families is largely attributed to home ownership and traced to New Deal policies designed to create “a white, asset-based middle class.”

9:00- How to fix: “There’s no quick fix for the inequality that has grown out of racial segregation.” “There are certain enabling goods and services that people need in order to thrive.” “Government . . . can facilitate it today . . . this time, . . . in a way that is inclusive.”

9:43 Ladera community signature drive to change the neighborhood covenant. “We had the power to get rid of it.”

I promised additional layers to the housing discrimination story. Here are two important additional links and a coda.

This 2021 story from NPR’s Morning Edition provides additional background on housing covenants. Before the New Deal institutionalized racial homeowner restrictions at the national level, property associations created them and courts allowed them by the 1920s. The NPR story names important litigation running from the era of covenants (approximately 1926 to 1948) to the era when housing discrimination became unenforceable (1948), and later illegal.

Until I read the NPR story, I had no idea that litigation from the family of Lorraine Hansberry, a playwright I teach in American literature classes, might explain why I received a copy of one of these racist covenants when I bought my first home, a house built in 1947, but when I moved two blocks away in the same neighborhood, to a house built in 1949, I did not receive another copy of the same covenants. It was such a relief not to see that horrid language twice. So now is as good a time as any to say: Thank you, Mr. Hansberry. (Also, a big thanks to the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, passed at the shockingly late date of 1974, which gave single women the right to have mortgages. But that’s another story.)

As for my 1947 house and other houses like it, according to NPR, racially discriminatory covenants are not as easy to remove as the RetroReport video might lead us to believe. Attorney Maria Cisneros, who found racial covenants attached to her home near Minneapolis, founded Just Deeds to help other communities get rid of unjust and now illegal language.

But there’s one final observation to make about the pre-history of the Ladera subdivision in Silicon Valley, bringing us back around to today’s theme of cooperation and dignity for all.

According to Jackson J. Benson, a biographer of the novelist and Stanford creative writing professor Wallace Stegner (recall: he was one of the original Ladera land investors who were denied FHA mortgages), soon after World War II, Wallace and Mary Stegner joined a housing association near Stanford with the intention of building their first home in a cooperative with no restrictions based on race or religion. Both the Stegners had personal interests in cooperatives. Wallace had been raised a gentile among Mormons in Salt Lake City, and Mary “was a socialist” who had worked with cooperatives “for several years” (Jackson J. Benson, Wallace Stegner: His Life and Work, 1996, p. 141).

Earlier in the 1940s, Wallace Stegner had completed a series of articles for Look magazine on racial and religious prejudice in America. Although his language is dated to the era, in this project he expressed racial self-awareness usually associated with the Civil Rights era: “The germs of prejudice are as common as those of tuberculosis,” he wrote. “[M]ost of us under the x-ray would show the tubercles of old infection” (p. 150). He cautioned against the kinds of actions (use of racial slurs, “feeling superior,” etc.) that “preserved” “the hard and durable spore” of infection found in “most of us.”

Benson’s biography corroborates the RetroReport story that the cooperative investors of Ladera Phase 1, who endured other “delays and disagreements,” had to abandon their construction plan once the FHA denied mortgages for lack of “exclusionary rules” (p. 153). As Benson wrote, “The Stegners, along with the other members, stood firm that they would accept any member regardless of race or religion. Without the FHA loans, building was impossible,” so “the association was abandoned, and the land was eventually sold to a developer” (p. 153, italics mine).

Incidentally, Benson records that it was Stegner’s idea to change the name of the residential community from “Lark Hills” to “Ladera”—“hillside” in Spanish (p. 153). Ironically, when the co-op failed, the Spanish word, Ladera, was retained as a name for an all-white subdivision—an act of cultural appropriation. Had the co-op succeeded, the Spanish word would have represented the inclusive intentions of a multi-racial, multi-religious co-operative founded before the Supreme Court ruled racial covenants unenforceable in 1948.

Like the Black and white organizers of the 1865 memorial for fallen Union soldiers, the California housing association of the mid-1940s represented a small effort at cooperation and peace-making in a larger environment of suspicion and discrimination.

Maria Cisneros and the 23 participating cities of Just Deeds have created a space where these cooperations can happen today.

Recap of today’s external links:

“The Overlooked Black History of Memorial Day,” by Olivia Waxman, Time magazine, 2020 (Thanks to

for this link.)“Whites-Only Suburbs: How the New Deal Shut Out Black Homebuyers,” by RetroReport, 2022.

“Racial covenants, a relic of the past, are still on the books across the country,” by Cheryl W. Thompson, et al., NPR Morning Edition, 2021.

Jackson J. Benson, Wallace Stegner: His Life and Work, 1996. Available from Better World Books and other retailers. See also Philip L. Fradkin, Wallace Stegner and the American West, 2009, from University of California Press.